THE MAKING OF SILO

Panavision Featurette

1) How would you describe the look that you wanted to achieve?

Finding the look and feel for Silo meant finding the emotional center of the film. I believe in being vulnerable behind the camera to better understand how the characters in front of the camera are experiencing their own vulnerability, challenges and fears.

On Silo, director Marshall Burnette and I wanted a warm, timeless, and filmic 35mm look that was built on the stress and anxiety of the storytelling. There is a timeless look to Panavision lenses. When you place the lens on the camera it is like stepping back in time to your childhood and seeing the classic iconography of film history. Amongst the beauty of Americana farm life, there is a darkness. Beside hay bales and horseshoes, there is punk music, southern attitude, and complicated wounds from the past that are reopened by the active danger.

I am a big proponent of genre bending stories. Drama without action is just drama and action without drama is just action. Throughout the process of making a film, I am asking myself how our choices impact the characters. I have always felt the conflict in a film as told through a reflection on the human experience allows us to begin to have catharsis and truly embody the hurdles our characters must overcome. Then once we are emotionally invested, we as the audience can see our hero face their challenges and we care on a much deeper level. I tried to incorporate this rhythm into my camera placement and lighting. In the end, Silo is a rescue film that is told by oscillating as a drama.

2) What were your visual inspirations?

There are two physical and emotional worlds that exist in Silo, outside of the “Silo”, and inside of the “Silo.” Inside, Cody fights for his life over 24 hours. Outside, his family, friends, and a complicated group of local town first responders fight for how they feel they can best serve the boy. Each of these worlds needed to stand on its own, while at once having visual continuity.

I had looked at a lot of drama and rescue films. They were all very cold, dreary, and uninviting. We wanted to create a warm and gentle look that also had an aged patina to it. We decided to push the digital negative stressing the image. We built the look of Silo off of the same stress and timeless world of hundred year old groves and rolling hills of Kentucky where farming has sustained communities for generations. The corn, being a faded golden color, created a natural warmth inside of the Silo. I decided to build off of this and mirror the warmth inside the silo, outside under the hot Kentucky sun. This tied the two worlds together nicely. There is an innate beauty to farming and also a hidden darkness and danger. The mantra in the film from Jr. played by Jim Parrack was, “how could something so selfless and something so simple could go south so fast?”

One of my all time favorite films is Days Of Heaven. There is a warm patina and ethereal spirit to the camera work of Nestor Almendros I have always admired. I wanted to borrow cues from that film, and contrast those cues by introducing the oscillating ferocity in the work of two great DoPs, whose work I have been so impacted by over the years, Masanobu Takayanagi, ASC, Out Of the Furnace and Greig Fraser, ACS, ASC, Killing Them Softly. I spoke with Greig about shooting on the Panavision High Speed Auto Panatar Lenses and he told me, “They are like the salt and pepper in the meal.” I chose those lenses.

3) Why did you choose to work with Panavision for this project?

On Silo I had a dual interest in paying homage to the world of farming communities around the country, who often pay the ultimate sacrifice to put food on the table for us, while honoring the delicate emotional arc of each of the character’s journeys. To complete both tasks required a major technical endeavor and a trusted camera partner. The obvious choice was Panavision.

This was the first time a motion picture had been filmed inside and around a grain bin “Silo” nearly in full. To make production more complicated the film takes place in one day over a 24 hour period.

We had three main sets that required three very different camera and lighting techniques: Our Practical Farm Silo Set with our 50’ tall grain bin; Our stage with our Silo Interior Set; and our Top Of The Silo Set, a 360 degree blue screen.

Since the Practical Farm Silo Set was massive, it required designing the shooting schedule to consistently emulate certain times as they occurred in the script, returning back to areas of the farm to allow the script to progress day after day. This was also an active farming operation, which meant safety was a major priority and our schedule was tight.

For the stage sets, we engineered a private jet hangar to suit our two stage needs by amending the structure with hundreds of feet of truss and chain motors, connecting all of our Quasar Science lighting to DMX control.

Our Silo Interior Set was lit by a main source, a daylight balanced Molebeam skip bouncing off of the corn, creating an ethereal shaft of light from the Silo door hatch above. As the day progresses the sun moves and so does this ray of light.

Throughout shooting, our cameras moved from dolly, to techno crane, to sticks, to handheld.

The Panavision team made sure we had exactly what we needed every step of the way on Silo.

I want to thank Director Marshall Burnette for trusting me with this powerful story and my entire technical team headed by 1st AC Geoff Storts, Gaffer Mattie Ware, and Techno Crane Operator, Scott Buckler.

CLICK HERE TO VIEW THE PROJECT

SILO - FILM STILLS

SILO - BEHIND THE SCENES

THE MAKING OF PEACOCK KILLER

ECA ICG: The International Cinematographers Guild Magazine Featurette

1) Peacock Killer earned you an Emerging Cinematographer Award, what is the most important thing we should know about the film?

Peacock Killer is an adaptation of Pulitzer Prize-winning playwright and Oscar-nominated actor Sam Shepard’s short story Peacock Killer from his 1974 book Hawk Moon. Actor/Director Boyd Holbrook made his directorial debut by adapting the story into a screenplay, Peacock Killer. This film was shot in the dead of winter in a remote town on the tips of the Finger Lakes in upstate NY. It snowed every single day of production and generally was 5F during the day and -15F at night.

2) What are the major themes of Peacock Killer?

The stories I am attracted to are those that are timeless and are able to break genres. Peacock Killer is about the close bond between a man and his dog and the limits to which he will go to save it. They embark on an unlikely journey of reconciliation. The film stars Shea Whigham (Boardwalk Empire, Silver Linings Playbook ) and Elizabeth Marvel (House of Cards, Homeland).

3) What sequence are you most proud of?

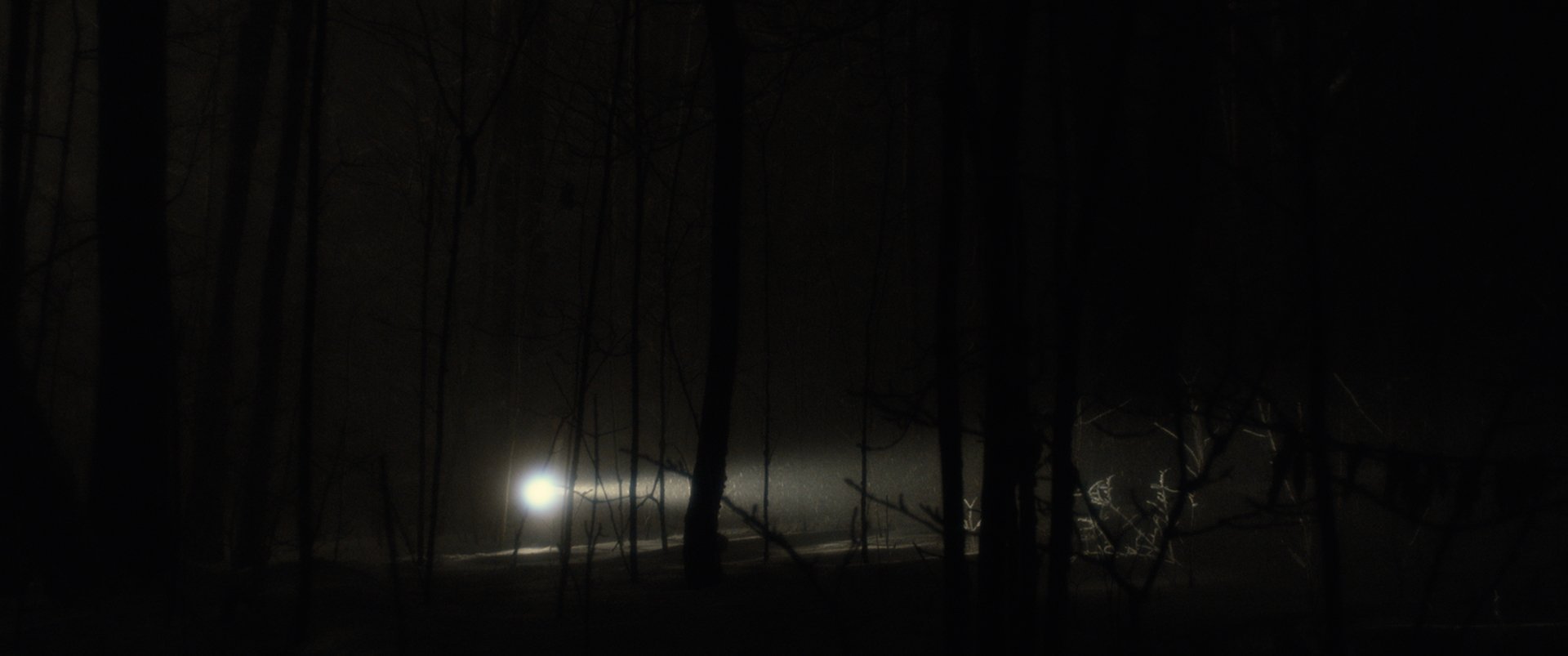

Startled in the middle of the night by an unfamiliar sound “Man,” played by Shea Whigham, must go on foot through the dense backcountry in an effort to find and kill the peacock that is tormenting him and his dog. There was about 5’ of snow on the ground and a major blizzard forecast for this night of filming. We needed a 100’ tracking shot at this very remote location. So we decided to lay the track on a private snow covered road adjacent and looking into the woods where Shea would walk. We wanted this scene to be dark, similar to the rest of the film, but also to be able to see our character and his performance. I remembered Roger Deakins had written about the night sequences in the desert on No Country For Old Men using large sources to catch moisture in the night’s sky. It was about -15 degrees with heavy snow coming down all night. Luckily at this location, deep in the woods, the ground banked downwards towards a river and with my gaffer Ben Carey we decided to place a row of 4K HMIs gelled ¼ CTO pointed upwards into the night’s sky. This gave the deep background a beautiful and very soft edge. To light Shea, who was wearing only long johns in the freezing cold, we used a high-powered flashlight that he carried (similar output to the one seen in Jurassic Park). The flashlight kicked off of the snow below and a small piece of show card carried by the grips helped to give him a beautiful, soft key from below. A very subtle smaller backlight for him was placed at one end of the track to fill in on some of the shadows.

4) What was the biggest artistic, logistical or technological challenge on this project and how did you overcome it?

The extreme temperatures below freezing. I remember it was so cold the fluid in the O’Connor 2575D head froze.

5) What is your style of cinematography?

There is a sequence where Shea Whigham is driving down a country road bringing his dog to the hospital in the middle of the night with intermittent street lights. We simulated the hard street light with carefully placed mighty 2K Blonde's, 12 or so along the road, the stands camouflaged and units at an attractive angle to get the light into the picture car. The result was passing light that would leave Shea dark and then slowly illuminate him as he approached the next source. That’s a good way of describing my style. I’ve always had a story first mentality. That means scouring the earth with your director for the perfect locations, then getting in that space and feeling both the practical and imaginative lighting you want to implement. Lens choice and camera placement has always been paramount to me. Most of Peacock Killer is shot on a 25mm Bausch + Lomb Super Baltar prime. My work is present and I often use POV in ways that brings audiences closer to the characters.

6) Where do you typically find inspiration for your work?

Vulnerability is how I create my work. The ability to read material and transpose a deep connection to my emotions in which the story can strike a cord. I try to turn that vulnerability and emotionality into causality and a conviction for why the light should have a certain quality and how the camera and the actors will dance. I feel cinematography is more similar to music than to painting. It’s rhythmic and has a cadence.

7) How has technological innovation affected cinematic artistry for good or ill?

Technology advances society and art. Film and Digital are two different mediums. Do I like the depth of color, consistency, and surprises of film, of course. But do I like digital capture and the ability to have more takes and see the image with a great LUT, yes. As long as the camera has a vintage lens on it.

8) What is one piece of gear you absolutely cannot live without?

I cannot live without beautiful vintage glass. Lenses are the real instruments of our craft. It’s like a piece of music. You can play it on a piano or a violin. But if you play the same piece of music on an electric guitar you might discover something with the same structure with an entirely different feeling. Whether you want a clean, organic or dirty look for your project, there are vintage lenses that can get you there. I don’t see any personal reason in my work to have to shoot on modern glass.

9) What does winning an ECA mean to you?

My dream has always been to help bring great stories to life. The International Cinematographers Guild and ASC represent the best in the craft of cinematography. To receive this award is an honor and a privilege; affirmation that I am on the path and encouragement to work harder each day.

10) If you could only give one piece of advice to creative/artistic young people, what would it be and why?

Everything in my life is credited to great mentors allowing me to witness them in pursuit of expressing their own craft and allowing me to build the tool set for the choices in my own work. My mom and dad really taught me to work hard and follow my dreams.

11) What else should the world know about you?

I am a swiss army knife with a heart.

CLICK HERE TO VIEW THE PROJECT

PEACOCK KILLER - FILM STILLS

THE MAKING OF THE BLESSING

1) What was the motivation around the cinematography of The Blessing?

The Blessing was conceived as a Visual Experience from day one that would marry the use of intimate camera work reflecting on subtle interpersonal family moments against the large backdrop and beauty of the Navajo Nation. All while showing the present impact of large scale surface coal mining that has left a 30 x 30 mile scar on sacred land. Every aesthetic choice in The Blessing was considered and curated from a story first approach. The importance of the dual role of cinematographer and co-director allowed us as filmmakers to gain unprecedented access and have the camera present in the most sensitive of moments. This choice also allowed the acquisition format to supersede the norm of prosumer camera equipment and bring the large scale professional Arri Alexa Super 35 format to capture these moments.

2) How did you craft the look of The Blessing?

Almost the entirety of the film is shot on the 1970’s Bausch & Lomb Super Baltar 25mm Lens. In most scenes the camera exists only several feet from the characters. By bringing the camera physically closer to the subjects, this wide perspective inturn brought the viewer much closer to the character’s lives. In the film you experience the world in an almost first person viewpoint for each sacred song, prayer, and blast in the coal mine. Through intimate camera work we were granted access to the sweat lodge ceremony where we filmed Lawrence performing a spiritual cleansing of his sins digging, drilling, and blasting into Mother Earth. In the climax of The Blessing, after surviving a life threatening injury at the mine site, Lawrence goes to one of the Navajo Nation’s four sacred mountains. He stands before the mountain and prays for forgiveness in his last attempt to regain his spiritual center. Lawrence breaks down in emotion and tears as his life has reached a pivotal moment that he cannot turn away from. We witnesses and filmed in a respectful and elegant demonstration of camerawork balancing wider moments of man vs. mountain with close ups of Lawrence reaching this critical moment.Using modern camera technology and lenses of the 70’s era created a balanced palette of modern and vintage; as the coal mines, vehicles and homes on Navajo Nation were largely built in the golden years of the western coal industry ie. 1970’s. The film works to mirror new and old visually by reflecting on the many ways the physically changing landscape of Navajo Nation has been altered forever and the remnants that remain are maintained by our First Nations people.

2) What was the duration of principal photography on The Blessing?

The Blessing was shot over 5 years of arduous trips to the northern Arizona desert of Navajo Nation. With a crew of almost always two, Jordan Fein and I worked to perform the almost impossible task. Each day we set out with Lawrence into the unknown, sometimes driving for 5 hours just to reach “town” for basic supplies like hay, water, and food. Other days collecting coal in the freezing winter temperatures to deliver and heat the homes of Navajo community elders, some the last remaining bearers of sacred stories and language. Most days began at 4:30am as Lawrence stood facing the east singing the Navajo Horse Song, followed by morning prayer with his family. The Blessing was largely shot between the hours of 4:30am-7:30am and 6:30pm-8:30pm during the dusk and dawn of magic hours. These were the fleeting moments of Lawrence coming and going from home to work and back to provide for his family. These peak hours in turn provided a critical capture window that was meaningful and visually stunning.

3) How did such long duration of principal photography impact your relationship with the film’s subjects?

The 5 year duration of filming allowed for the privilege of building a deep and important relationship with another major character in The Blessing, Caitlin Gilmore. Caitlin is Lawrence’s youngest daughter and final child of five to depart the homestead in search of opportunity off of the Navajo Nation. Through intimate camera work and trust between subject and filmmakers, Caitlin made an active choice to share her sexuality and come out as a gay woman on camera. While maintaining this aspect of her identity as a secret from her dad. Caitlin wanted the camera to capture this moment in a letter she wrote and read aloud to the us as filmmakers. It was at the World Premiere, at Full Frame Documentary Film Festival on a stage in front of hundreds of moviegoers, family, and Lawrence that this visual moment was revealed in the film, through Caitlins wishes for her father to experience. Without the camera’s presence, that it's possible she may have never shared her true self with the world.

CLICK HERE TO VIEW THE PROJECT

THE BLESSING - FILM STILLS

THE MAKING OF IINNIIWA: THE BLACKFEET BUFFALO STORY

MOVIEMAKER MAGAZINE FEATURETTE

1) Can you talk about how Yo-Yo Ma came to be involved in this project?

Yo-Yo Ma has been an advocate of this restoration effort for years, wanting to honor the power of relationship with these sacred buffalo relatives, called “iinnii” in the Blackfoot language. In May, Yo-Yo Ma traveled to Blackfeet Nation to add his artistry to the chorus that calls to the sacred buffalo relatives. Yo-Yo performed “Amazing Grace,” a medley that provides hope and unity during divided times. The film culminates in three parts – IINNIIWA: The Blackfeet Buffalo Story, Act I, Act II, and Act III. Act II is a documentary that will premiere in New York City and in Montana on Blackfeet Nation. Santa Fe audiences will see Act I during Santa Fe International Film Festival.

2) How did you and the other filmmakers get involved?

We were honored to have Chris Eyre [Smoke Signals, Dark Winds] as our Executive Producer, serving a crucial role for the film. He had a vision of these sacred relatives on their journey back home. In a dream moment, Yo-Yo shows a sign of respect and honor by touching forehead to forehead, a connection that unites heart and soul. This scene is meant to evoke a time when people and animals lived in close relation with one another. My dual role as cinematographer allowed me to observe, respect, and honor these iinnii buffalo. The collaboration between Elias and me meant a closer lens on the vital nature of this story.

3) The Buffalo, were any VFX used to capture so many of them running together?

I can say with immense gratitude that all of the scenes of buffalo running through the landscape were filmed in-camera. This is a tremendous thanks to the Blackfeet Buffalo Program and fantastic wrangler team who raise and care for the Buffalo as they are guided towards their rewilding release. The Blackfeet Buffalo Program has been at the forefront of returning buffalo to the Blackfeet territory for more than two decades. In June 2023, the Program made history by returning 49 iinnii to their homelands at the base of Nínaiistáko, or Chief Mountain—a site sacred to all Blackfeet. The homecoming was a moment of fruition for the long-time partnerships between the Blackfoot Buffalo Program, Blackfeet Fish & Wildlife, Glacier and Waterton Lakes National Parks, and the Native-led nonprofit Indigenous Led.

4) Is the scene when Yo-Yo Ma touches the buffalo real? How did you accomplish it?

Yo-Yo Ma is a wonderful human radiating positivity in every direction. Of course, safety was a big concern for the shoot. As producers, we don’t encourage anyone to ever touch buffalo. They should always be observed and respected from a safe distance. This scene is a dream and meant to represent a time when people and animals lived in close relation with one another. The film does have some movie magic to capture this scene safely. As we filmed Yo-Yo’s performance, it actually evoked a real reaction from the iinnii buffalo nearby and they made their way closer and closer to Yo-Yo. It shows that music has the power to unite.

5) Can you detail the Santa Fe connection to the film?

Chris, Elias and I are based in Santa Fe, New Mexico. We have a wonderful filmmaking community here that supports and respects Indigenous stories. I have been working in the Southwest for 13 years, spending extensive time on Navajo Nation. After a decade, I came to Santa Fe and discovered for myself the passionate community of art supporters.

6) Can you tell me a little more about Indigenous Led?

Indigenous Led is a native-led nonprofit organization whose work is focused on science, youth and the rematriation of buffalo on Indigenous lands. Their work is extensive across the country. They support and believe art and film have the unique ability to unite, heal, and evoke a conversation around meaningful change. The best part of this project was really learning about the youth of Blackfeet Nation. For around 150 years, buffalo have been gone from these lands. Multiple generations grew up, lived and passed on without ever seeing their sacred iinnii relatives, an animal that is directly tied to their Blackfoot language and origin story. Now, thanks to these wonderful organizations, the youth are growing up with buffalo around them, on their lands, and in their ceremonies. The return of buffalo is giving the youth a way to connect with their origin story, their Blackfoot language, and their ancestry. This effort begins a process of healing generations of destruction and looks toward a brighter future.

CLICK HERE TO VIEW THE PROJECT

IINNIIWA: THE BLACKFEET BUFFALO STORY - FILM STILLS